Implementing C++/C# interop for Linux

posted on April 19, 2023

#systems #cpp #csharp #linux #researchI was pretty surprised to find a lack of good C++/C# interop resources online for Linux, given that most of the online tutorials were for C++/CLI, which only works with Windows. Here, we'll explore the basics, internals, and gory bits like making pointers to native memory safely, with some remarks on performance.

Getting started

If there's one thing I could convey before skimming the article or moving onto another blog post, if you're looking to make C++/C# interop work on Linux, ignore any resources to do with C++/CLI. C++/CLI is a part of the Common Language Infrastructure and built into Microsoft's Visual Studio, but they have no plans to include it in .NET Core anytime soon.

To get started, you'll need:

- Linux OS installation

- Your favorite C++ compiler

- The .NET SDK

Managed and unmanaged code

Some key vocabulary to know when delving into C++ <-> C#/Java interop are the notions of managed and unmanaged code. Unmanaged, or "native" code is executed directly by the operating system without the use of any runtime environment: think low-level or assembly languages, or languages typically directly compiled to Assembly such as C++ or Rust that can be executed by the CPU without any intermediate steps.

On the other hand, managed code refers to, you guessed it, programs executed within a runtime environment such as the .NET Framework or the Java Virtual Machine. These programs have automatic memory management, security features, and other services, but with no free lunch—also incurring an additional overhead. A common design pattern among managed languages is just-in-time compilation (JIT). Managed code compiled in the runtime environment is first transpiled to an intermediate language: in C# specifically, this is the .NET Common Intermediate Language (CIL). Once the code actually needs to be run, it is compiled to native assembly, which can actually be executed by the CPU. This is convenient to make sure your code "just works" in all environments, as long as they offer .NET or JVM support or whatnot.

Our goal here is to allow communication between the managed and unmanaged parts of a codebase. In this article, I will use {C++, unmanaged} and {C#, managed} interchangably.

Basics of marshalling

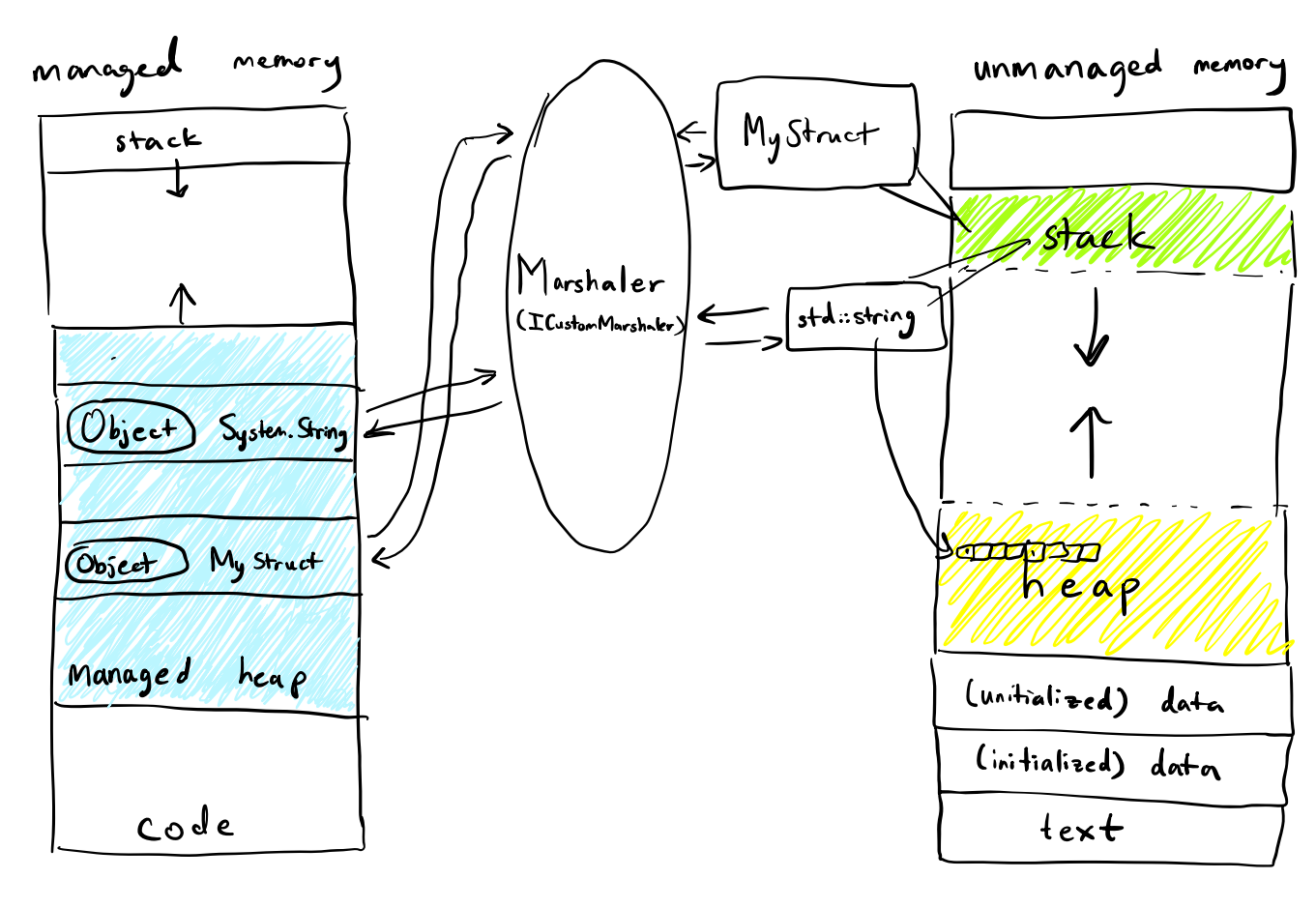

One more thing before we get started with the actual interop code. To get a good footing on the

performance of interoperability between C++ and C#, we need to talk about marshalling.

Marshalling is the process of transforming data between different representations or formats between

two languages. Unfortunately, a std::string from C++ isn't so easily passed over to C# without

extra work: std::string differs highly in representation from compiler to compiler, and more

importantly, is within unmanaged memory; the System.String data in C# are garbage collected and

do not have an explicit memory address on the heap, and is subject to change at any time during

program execution.

If you want the simplest plug-and-play between C++ and C# types, you can use the MarshalAs

attribute when passing managed data types to unmanaged code that have predefined marshalling rules

(these are implemented through the ICustomMarshaler).

The interface is as follows:

MyFunction(char* string) // Within some C++ DLL.

MyFunction([MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPStr)] string) // Within some C# DLL.

The Unmanaged.LPStr indicates that the C# string should be marshalled as a null-terminated ANSI

string, since the C++ side expects a traditional C string. See below for a diagram on

how it fits all together with respect to memory layouts!

Insight: Make sure to marshal types between C++ and C# that are not blittable; see next section for the definition of this.

Blittable types

Many common data types have a common representation in both unmanaged and managed memory, and do not require special handling by the interop marshaler. While they may still be copied, each of them have a tiny representation in memory so it can be done exceptionally efficiently. The blittable types are listed below, with their C++ counterpart:

// preferring standardized types which don't differ based on implementation

System.Byte <-> uint8_t

System.SByte <-> int8_t

System.Int16 <-> int16_t

System.UInt16 <-> uint16_t

System.Int32 <-> int32_t

System.UInt32 <-> uint32_t

System.Int64 <-> int64_t

System.UInt64 <-> uint64_t

System.IntPtr <-> void* // or any pointer type, but will be an opaque pointer in C#

System.UIntPtr <-> void*

System.Single <-> float

System.Double <-> double

Insight: Prefer blittable types in interop scenarios whenever possible, whether it be function parameters or struct fields. If you have extremely complicated data structures, try to break down function calls between C++ and C# to the truly necessary parts.

Your C++/C# interop options

Platform Invoke (P/Invoke)

Platform Invoke (P/Invoke) is a built-in interface in the System and

System.Runtime.InteropServices namespaces of C#, so no external installation required.

The mechanism is very simple for calling unmanaged code from managed code, but going the other

way around is a little verbose.

Calling C++ (or even C) code from C#

To start, let's define a C++ library for use in C#. A very important thing to note is that all C++ code must have C-style linkage in order to be used in C#.. This means that you cannot use templates or other C++ constructs explicitly in your function.

// Need to use extern "C" to give any exported functions C linkage.

// To clean up your code, I usually use a macro: #define EXPORT extern "C"

extern "C" int add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

Now, compile the C++ code to a dynamically-linked library (DLL). This allows external programs

to call into the function through a given file, usually in .so format. Using gcc,

g++ -c -fPIC example.cpp -o example.o # Compile the code without linking it into an executable

g++ -shared example.o -o libexample.so # Link the object file into a shared library

Call into it in C#:

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

class ExampleCSharpApplication

{

[DllImport("libexample.so")]

public static extern int add(int a, int b);

static void Main(string[] args)

{

int result = add(2, 3); // this is executed in unmanaged code

Console.WriteLine(result);

}

}

Calling C# code from C++

On the other hand, calling C# code from C++ is a little more complicated. Given some managed code you want to call, you will need to create a delegate and pass it as a callback to the unmanaged side. See below for a working example.

// ExampleCSharpLibrary.cs

// This is the main C# library we want to wrap and call in C++.

using System;

public delegate void MyDelegate(int arg);

public static class ExampleCSharpLibrary

{

public static void MyMethod(int arg)

{

Console.WriteLine("MyMethod called with argument: " + arg);

}

}

In this example, we're defining a delegate type called MyDelegate. We're also defining a static

method called MyMethod, which has one (blittable) argument for brevity.

Now, export a function in C++ that takes a function pointer as a parameter:

// ExampleCppApplication.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <functional>

typedef std::function<void(int)> MyDelegate;

extern "C" void CallManagedFunction(MyDelegate callback)

{

callback(42);

}

Finally, to actually invoke the C# code in C++, you'll need to have a higher order function

that wraps the MyDelegate function type. This allows the C++ code to use CallManagedFunction

to call MyDelegate.

// ExampleCSharpApplication.cs

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

class ExampleCSharpApplication

{

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.Cdecl)]

public delegate void MyDelegate(int arg);

[DllImport("ExampleCppApplication.dll")]

public static extern void CallManagedFunction(MyDelegate callback);

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MyDelegate callback = new MyDelegate(ExampleCSharpLibrary.MyMethod);

CallManagedFunction(callback);

}

}

Insight: Use P/Invoke as a first choice if C++ headers are installed as system headers, which make their shared libraries accessible by name. Also, all C++ exported functions must have C-style linkage.

Command Language Runtime (CLR) Hosting

If you don't know the name of your C++ DLL a priori, or you want full control of the lifetime of the .NET runtime environment, go with common language runtime (CLR) hosting. Essentially, this entails writing custom infrastructure to load the CoreCLR components and start the runtime.

I've implemented this as part of my research, and one of the few useful articles I've found is by Igor Ladnik on CodeProject. Read more here.

Gory stuff: working with native memory in managed code

If you don't plan to use C++/C# interop for extremely performance-critical scenarios (below the ms level), you don't need to read this section.

However, if you're in a position where avoiding the overhead of a memcpy is essential, you will

absolutely need to access native memory via pointers, as marshalling data has a copying overhead.

Pinned memory and unsafe

C# offers us the awesome (and dangerous) option to allocate unmanaged memory within managed code

through the unsafe keyword and the System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal library. By using

the unsafe keyword, a C# function can use pointers just like C++:

// Note the `unsafe` keyword, which allows us to use pointers.

unsafe static void Main(string[] args)

{

int x = 10;

int* p = &x;

*p = 20; // x now stores 20.

}

From our discussion of managed and unmanaged code, managed code is usually marked by using garbage

collection. With garbage collection comes great liberties, but less guarantees: managed objects

are commonly moved around to avoid fragmentation and to allow optimizations. So our pointer p

might get garbage collected during execution. To avoid this, we have two options (1) use the fixed

keyword, to explicitly pin the pointer within a given scope, or (2) using GCHandle to pin it

so it can be passed as a variable. I prefer (2), since we typically want to pin memory longer

than the execution of a single function anyway. Just make sure to free the pointer before you're

done with Marshal.FreeHGlobal.

This allows us to allocate native memory with Marshal.AllocHGlobal and convert C# structures to

pointers through Marshal.StructureToPtr, among much more.

Safely handling pointers

A useful construct to follow when working with native memory pointers owned on the C# side is to use a try/catch/finally structure, as in the below code I used in my Cascade research:

IntPtr emitKeyPtr = Marshal.StringToHGlobalAnsi("some string");

IntPtr emitBytesPtr = Marshal.AllocHGlobal(1);

try

{

Int32 val = 1;

Marshal.StructureToPtr(val, emitBytesPtr);

emit(emitKeyPtr, emitBytesPtr);

}

catch (Exception)

{

Console.WriteLine("Exception caught when emitting data.");

}

finally

{

// Avoid memory leaks by freeing all memory allocated here.

Marshal.FreeHGlobal(emitKeyPtr);

Marshal.FreeHGlobal(emitBytesPtr);

}

Consider if we reach an exception and execution is interrupted after the memory is allocated to either the key or bytes pointers, which are passed to the emit function. Then, we will never have deallocated memory, and resulted in a memory leak. The finally block ensures that we don’t forget to free the memory in either case after they are used in the emit function.

Case study: Cascade

The original purpose I had for implementing C++/C# interop was for the Cascade system. Cascade is an ongoing research project, using RDMA to to enable super fast operations in distributed memory. You can read more about how I did it in the paper I wrote here. There's also a good bit on the performance of the system, which is based on hosting the CLR.

Also, the Cascade GitHub repo is here, if you'd like to see the progress. Thanks for reading!